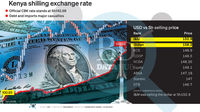

The Central Bank of Kenya this week shocked the market with one of the steepest increases in its benchmark lending rate. This saw the rate hit the highest point in 11 years as Kamau Thugge, the governor, moved to curb inflation and stop the free fall of the shilling. This is after the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) increased the CBK rate to 12.5 percent from 10.5 per cent, the highest since September 5, 2012, when it was at 13 percent.

Dr Thugge spoke to the Business Daily on the MPC decision even as he faulted his predecessor on what he thinks was Patrick Njoroge’s bungling of the exchange rate.

You started at CBK with a meeting outside the bi-monthly monetary policy committee meeting cycle where you increased rates. Later, you introduced a corridor to anchor the interbank rate. Now you have the highest rate hike in a decade. Just how much was monetary policy under your predecessor misaligned?

I think my brief speaks for itself. I do think that the exchange rate had been overvalued for quite some time and perhaps we didn’t raise the interest rates as soon as we should have and so even with this 200 basis points increase it kind of takes us back to the interest rate differential at least from policy rates before the US started to tighten their policy. We are kind of still behind the curve in the sense that the US had already raised rates so in a sense this establishes some kind of a parity. We expect two things, one is possibly a slowdown in portfolio outflows and maybe an increase in inflows compared to the current situation.

You are on record saying the shilling was overvalued for quite a while. How exactly did this happen?

Yes, I am on record saying the exchange rate had been overvalued for some time. In my view, if you look at several indicators whether it is the share of exports within the East African Community; even go back like 10 years and just look at Kenya versus Tanzania and Uganda. Our share of exports was over 50.0 percent and it is now 39.0 percent. If you also look at our exports to GDP ratio, it has persistently declined from 12.0 per cent to last year’s 6.5 percent.

We’ve also looked at tourism receipts in relation to GDP and we are the lowest against Uganda and Tanzania. Then you also look at foreign direct investment and we are attracting much less than Uganda and Tanzania by a significant amount. All these are indicators of an overvalued currency. Now, how that was facilitated was that the Central Bank intervened quite significantly in trying to hold the shilling down.

In 2020, most of the interventions were one way; in other words, the Central Bank sold foreign exchange and in 2020 the Central Bank sold about US$1.3 billion. In 2021, another almost US$650.0 million. Cumulatively up to about May of this year, the Central Bank lost about US$2.8 billion. When the issue of the US tightening monetary policy and interest rates in the US going up came up, we were in a situation where we did not have any external buffers to just mitigate the impact.

Given what you have said and the wild depreciation we have seen on the shilling in 2023, where do you place the shilling’s valuation now? Still overvalued? Fairly valued? Undervalued?

Our view is that the exchange rate has now depreciated more than was required to re-establish an equilibrium and competitive exchange rate. Where we are now is a situation where there’s a lot of uncertainty because people feel they just don’t know where the exchange rate is going to end up and this has introduced a lot of uncertainty.

Because of that, you find that even foreign investors are hesitant about coming and they hold back on portfolio inflows and foreign direct investment. The same thing happens with domestic investors.

You came in when inflation was at 7.9 percent. It now stands at 6.8 percent. Are you happy with the progress so far and what is the magnitude of the exchange depreciation pass-through in the inflation numbers?

When I came in, inflation was headed in the wrong direction and at that time I felt it was important that we take very strong action to demonstrate our commitment to ensuring that we bring inflation back to the target range. To some extent, we have been able to do that, now it is within the target range but it is getting stuck on the upper end of the range, around near 7.0 percent and we don’t want expectations to be stuck and entrenched at that level.

It was important for us to be able to deal decisively with those inflation pressures and at that time the non-food, non-fuel inflation was also quite high and we knew we had to bring it below 3.0 percent which has broadly been consistent with the overall inflation of 5.0 percent.

So even this action of 200 basis points, in addition to addressing the pressures from the exchange rate on inflation, which was 3.0 percent points out of the 6.8, we are also looking at how to bring down further inflation pressures.

How much has the shilling depreciation impacted the fiscal agenda for 2023/24? The Treasury is on record saying that in the full year ended June 2023, the unit’s slide against the US dollar increased the stock of public debt by a staggering Sh883.5 billion?

Debt service is going up and complicating the fiscal consolidation, too. It is also significantly increasing our foreign currency-denominated debt. Right now we have about US$40 billion in external debt and every time the shilling depreciates by one shilling, our debt goes up by Sh40 billion. So you can imagine it depreciates by Sh10, that is Sh400 billion. That puts at risk our debt sustainability path.

It means that of the several indicators of debt sustainability like the net present value of debt to GDP where the threshold is 55 percent and the net present value of debt to exports where the threshold is 180 percent, the fact that the net present value of debt rises with the exchange rate means we stay above those thresholds for a much longer time and could result in unsustainable debt position.

Are we expecting any significant hard currency inflows in the near term?

We do expect some external inflows between now and the end of December 2023 and broadly we do expect a financial account surplus of just slightly over the current account. In other words, there are enough financial inflows to cover the current account deficit and have a surplus but that’s assuming we get the full amount of US$500 million from the Trade & Development Bank.

I put a caution there because that full amount may not come in, the latest information we have is that we may only get US$300 million within the first two weeks of December which still would translate to an overall balance of payments surplus of US$361 million.

By JULIANS AMBOKO