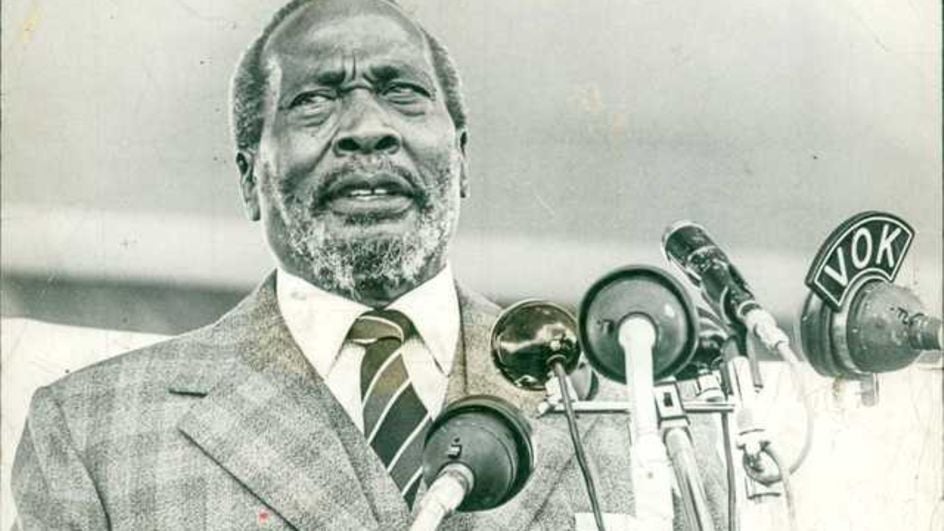

We shall build a country where every citizen may develop his talents to the full, restricted only by the larger aim we have of building a fair society.

There will be no privileges for any minority. Equally, we shall see that no member of any group undergoes discrimination or oppression at the hands of the majority – Jomo Kenyatta May 27, 1963, after Kanu victory.

On June 1, 1963 at the steps of today’s Harambee House, Jomo Kenyatta was sworn in by Governor Malcolm MacDonald as Kenya’s first prime minister.

Wearing a brightly coloured beaded cap — to match that of Kanu’s vice-president Oginga Odinga — Kenyatta was impressive with his ceremonial fly-whisk.

“This is one of the happiest moments in my life,” said Kenyatta. MacDonald described the occasion as the “grand hour in Kenya’s history”.

Shortly after, and in a sense of unity, Kenyatta, Odinga, Tom Mboya and James Gichuru — the doyens of Kanu — drove off in an open car to waving, dancing and cheering crowds. A new nation was just about to be born in a few months’ time.

Madaraka Day, as it came to be known, not only marked the day that Kenya’s constitutional journey towards independence gained a clear momentum, but also marked the time when the self-rule constitution, negotiated at Lancaster House in London, came into force.

TRIBAL FEUDS

Duncan Sandys, the Secretary for Colonies and the man who chaperoned the process, had sent a message to Kenyatta and which informed the thinking within the Cabinet on the future of Kenya.

“I trust all will work together and play their part in building a happy and united nation,” wrote Mr Sandys.

By default, Governor MacDonald had declared June 1 and June 2 public holidays and as the days of “national rejoicing.”

Keeping this hope alive, and after 57 years, has been one of the biggest tasks that has faced the various governments — from Jomo Kenyatta to Uhuru Kenyatta.

Jomo had been asked to form the government after the May 19, 1963, elections gave his party 58 seats in the House of Representatives against Ronald Ngala’s Kenya African Democratic Union (Kadu), which won 28 seats. At the Senate, Kanu had 11 seats against Kadu’s 9.

Inheriting a country that was awash with tribal feuds, Mr Kenyatta’s Kanu had crafted a manifesto that attracted votes from all tribes.

At the top of the agenda was not only national unity, but also the desire to address the inequities brought about by more than 60 years of colonial rule.

It’s a challenge that still dominates the national politics — and which has become a constant theme within political parties.

SHARING RESOURCES

In the current Constitution, the question is addressed under Article 202, which calls for equitable sharing of national revenue at the national and county governments level.

Also, county governments are given an additional share of revenue depending on their population and other needs.

Another highlight of the Madaraka constitution was on regional governments, which are today resuscitated as county governments.

While Kanu was determined to put in place a unitary state with a central government, Kadu had pushed, with Britain’s support, the idea of regional governments.

But the regions faced various handicaps, among them lack of funds and suitable administrators. Kanu had promised to change the constitution once it secured full mandate by December 12, 1963, and put in place a unitary state.

This debate (Majimbo) later became a bone of contention. Finally, the idea cropped up during the clamour for a new constitution to replace the independence era document and Kenyans overwhelmingly voted to test whether county governments would deliver on the development promise of self-rule.

LABOUR FORCE

Another promise made in 1963 was the training of local manpower. While the colonial government had failed to expand college and university education, the desire for local manpower turned out to be a major issue considering that most British administrators wanted to leave after independence.

The regional Common Services Authority had hired a Nigerian, J.O. Udoji to help address the manpower shortage problem and how to improve it across East Africa.

His final report of the Africanisation Commission said that people of doubtful character should not be anywhere near government coffers.

“A person of doubtful character must not be employed as a tax collector, nor should a dishonest person be put in charge of the Treasury,” the document said.

It further said that the standards set by the document should remain absolute: “We accept that standards of efficiency are bound to fall… but the standards should remain absolute where safety of life, honesty and integrity are concerned.

It is this challenge of integrity that now marks the most important aspect of Kenya’s political journey. With corruption eating the very base of our nation, dreams of founders of the nation look like a mirage.

President Uhuru Kenyatta has been fighting a rather lonely battle to rid his government of cartels and to streamline the way government does business.

CORONAVIRUS

President Mwai Kibaki faced a similar test during his tenure after throwing the independence party out of power.

Kanu, under President Daniel Moi, had not only run down the economy but was also accused of turning government institutions into cash cows for the political elite.

Jomo Kenyatta’s early promises included eradicating diseases and providing clean water, health facilities and energy.

At the moment, the government – like many in the world – has been tested with the emergence of Covid-19,which has not only disrupted the economy but also left millions jobless.

Another challenge, foreseen in 1963, is that of manpower. Although various institutions have mushroomed, the quality of education has been compromised – thanks to lack of integrity.

When Jomo Kenyatta formed his first government, he promised to rally all communities together in a bid to build one nation.

He had first to tame Kadu secretary-general Daniel Moi, who had on May 28 warned that a “civil war” would erupt if Kanu tried to upset the Lancaster Constitution.

COALITION BUILDING

But since the self-rule constitution did not have a clause on how it could be amended, Kenyatta had to wait until after December 12.

As Uhuru Kenyatta experiments with coalition building, his father did the same within the Madaraka Cabinet when he brought on board two europeans: Bruce McKenzie, whom he appointed Minister for Agriculture, and Peter Marrian, who became Parliamentary Secretary to the Ministry of Lands.

President Uhuru Kenyatta is also testing a similar coalition building within his party in a bid to streamline the workings of his government – and as he said last week, secure his legacy.

As Jomo Kenyatta went around the country preaching unity, it was a speech that he delivered in Nakuru on June 23, 1963 that indicated that those who wanted to divide the country would face his wrath.

“I would like to point out that the government, which is in power, is the government for the whole of people of Kenya. It is not just for those who elected us. We shall care for those who gave us votes and those who did not equally.

The opposition is formally recognised in our constitution and can play a constructive role in nation-building. On the other hand, we shall be as firm as any other government in dealing with anyone who turns to subversive action…we must not dwell on the bitterness of the past…let us look to the future of a good new Kenya.”

It is these aspiration of the founding father and the challenges that have come with it that have been driving the Kenyan nation — 57 years after we started the journey with self-rule.