The theme of the fifth Nairobi International Book Fair in September 2002 was ‘Reflecting on African History’. The five-day book extravaganza happened, as usual, at Sarit Centre in Westlands.

The Kenya Publishers Association organised a reflection in the form of a seminar and invited a cross-section of book industry stakeholders, including the Department of Literature at Kenyatta University.

I had just rejoined the department as a master of arts student, having graduated the same year. I was delegated, as a graduate assistant to the chairman, to attend the workshop and give a report on it.

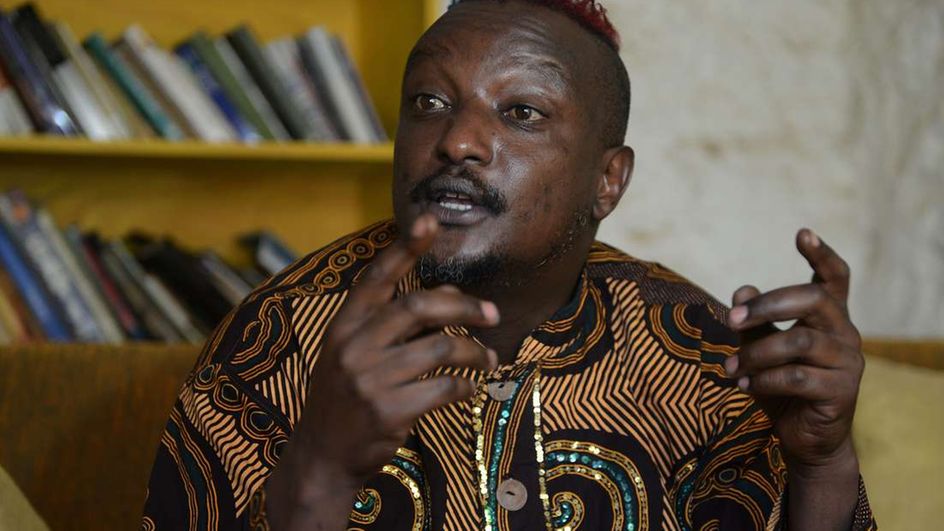

This was my first encounter with Binyavanga Wainaina, the iconic Kenyan writer who passed away a year ago, aged 48. In July 2002, he had been named the first Kenyan to win the Caine Prize for African Writing for his coming-of-age long short story “Discovering Home”.

I had heard about the feat of this new kid on the block from our modern African literature post-graduate seminars under the fecund Dr Garnette Oluoch-Olunya, currently affiliated with GoDown Arts Centre and St Paul’s University.

MARGINAL VOICES

We hit it off as friends immediately, reminiscing on growing up in Rift Valley – he in Nakuru and I farther west in Eldoret. We both were children of mixed-marriage families. We each had a Gikuyu parent. This explained his hybrid name from Uganda and Kenya that fascinated many for years.

He named me Wanjohi wa Makokha to highlight my bi-ethnic identity. Ambivalent identities were big themes in his mind.

Years later, he insisted I use this Luhya-Gikuyu moniker when I published my first book of poems, Nest of Stones (2010), which bears his benevolent endorsement on its top cover.

It is Binyavanga who egged me on to write a dissertation for my master’s on the notion of hybridity and cosmopolitanism in Kenyan literature. He wondered why East African Asian writers such as Yusuf Dawood, M.G. Vassanji and Ugandan Peter Nazareth, just to mention a few, remained marginal voices in our literatures.

Their writing espoused the ambivalent and urban spirit nourishing many inter-ethnic Kenyan families today, he mused.

Back then it was a new idea. I picked it up and wrote a dissertation on the early novels of M.G. Vassanji, later published as a monograph, Reading M.G. Vassanji: A Contextual Approach to Asian African Fiction (2010). Vassanji is the foremost East African Asian novelist today; he was born on Desai Road in Ngara, Nairobi, on May 30, 1950.

AFRICAN WRITING

We invited Binyavanga to share his reflections on new African writing at Kenyatta University on February 6, 2003. It became clear, even back then, that he was concerned about the conservative state of mainstream literary criticism at that time.

To him, emerging trends of African writing called for new critical lenses, including those that championed non-traditional voices, forms and styles.

Texts and their contexts together espoused the intellectual climate of their setting and time in history. He felt that the new century was offering a new chance to deconstruct the mainstream canon of the time. His talk was titled “New Trends in African Literature in the 21st Century”.

Binyavanga studied in South Africa and was newly returned in the country. His vision of renewal was informed by translational cosmopolitanism and urbanism common in Black South African culture, music and literature.

He stressed the important role of literary magazines as touchstones of new trends in societies throughout the history of African literature.

FOSTERING TALENT

Literary magazines and journals offer breeding grounds for new talent in societies under transition, he noted. Each generation needs journals to articulate their cultural aesthetics and ideologies of art just as Negritude poets needed Présence Africaine.

Closer, he singled out the transnational and seminal role Transition, edited by Rajat Neogy, a Ugandan Asian, had played in fostering creative writing at independence in our region in the 1960s.

Truly, in this same year, 2003, he walked the talk by establishing the literary journal Kwani? with others. Weight of Whispers, which won the Caine Prize that year, was published in it.

This story and the award set forth the literary career of its author, Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor, who rose to win the Jomo Kenyatta Prize for Literature in 2015 with her hybrid novel Dust.

Today, as Chimamanda is to Nigeria, Yvonne is to new Kenyan fiction: its new poster face. Her second epic novel, The Dragonfly Sea, embellished with history, hybridity and romance, is one of the many literary works penned by writers whose literary careers are affiliated to this journal.

LITERARY AWAKENING

Both Binyavanga and Yvonne became figureheads of a literary awakening at the turn of the century in Kenya. In the first decade of the new century, their literary achievements inspired several young creatives and critics who coalesced around their journal.

Its Nairobi headquarters at Madonna House became a literary mecca for contemporary writers even from abroad. Kwani? literary salons at Club Soundd on Kimathi Street became part of the vivacious cultural life of the city under the Rainbow government.

The annual Kwani? International LitFest cemented this historical role that Binyavanga and his associates played in fermenting new literary trends in Kenya at the outset of the century.

I was involved in organising the festival in 2005 after successfully defending my research thesis. Today, it is a year since Binyavanga left us. He had touched so many people in many different ways by the time of his demise.

The books and literary wisdom he left behind are now collected under one umbrella at Planetbinya.org. Scholars from Africa and beyond write academic papers on his literary oeuvre and propagate his social visions.

He remains that larger than life figure, having fractionally instigated our literary revival based on cosmopolitanism and urbanism as indices of our national culture and identity in this age of globalisation.