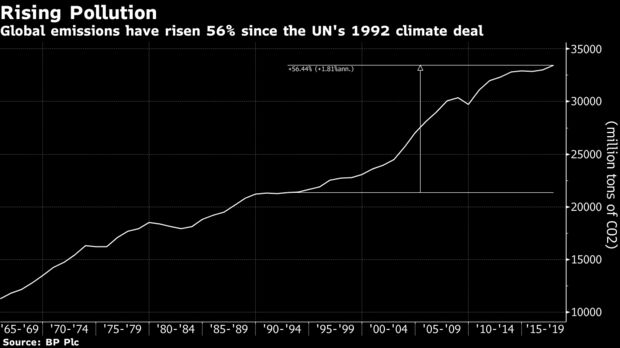

Envoys from almost 200 nations gather in Bangkok Sept. 4-9 to take the latest steps in the fight against climate change.

Convened by the United Nations, the delegates from energy and environment ministries are working on a rulebook to implement the landmark Paris Agreement, where countries rich and poor would work to cut heat-trapping pollution. The talks aim to lay the groundwork for the annual UN climate summit, which takes place later this year in the Polish city of Katowice.

“This session needs to make real progress on clarifying the myriad technical issues in the Paris rulebook negotiations and narrowing the options on the table so that ministers can reach political compromises on the various stumbling block issues,” said Alden Meyer, who has followed the talks for more than two decades at the Union of Concerned Scientists in Washington. “Adoption of a robust package of rules in Katowice is essential to building confidence in the Paris Agreement.”

1. What’s the aim of the Bangkok talks?

Civil servants are trying to agree on a set of rules that flesh out the 2015 Paris deal. What they produce will be fine-tuned and adopted by ministers at December’s higher-level meeting in Katowice. The co-chairs of the meeting have a difficult task on their hands. They must narrow an unwieldy set of working documents to something politicians can realistically agree on.

2. What happens if they can’t agree during these talks?

There will almost certainly be more talks no matter what the outcome in Bangkok. This group has been meeting for three decades, producing historic agreements every few years. It produced both the Kyoto Protocol as well as the Paris deal. The meeting in Poland “will be in jeopardy” if there’s no satisfactory outcome in Bangkok, the organizers of the group said on Aug. 16. In an unusual step, they indicated support for another round of discussions before December if needed.

3. Why has it been so difficult to reach an agreement?

There’s a lot to get through. And delegates are reluctant to agree on any single measure until everyone is happy with the shape of the whole deal. Developing nations want richer ones to make good on a promise for $100 billion a year in climate-related funding. Richer countries want developing ones do more to rein in their own emissions — and to open up to inspectors who can verify those cuts. Underneath those broad demands are thousands of details and aspirations needed to implement the Paris deal. And since that agreement came together in 2015, the nations at the table have drifted back into historic factions, bickering on issues including:

There’s a sense of an absence of leadership pushing for action, with U.S. President Donald Trump vowing to leave the Paris deal and Chinese President Xi Jinping focused other issues ranging from trade to foreign policy.

4. What’s the U.S. position at these talks?

While Trump has pledged to pull out of Paris, the U.S. remains a player at in Bangkok because it remains a part of the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change, the treaty that established the discussions. It also will take years to complete the withdrawal from Paris. That means Trump’s representatives remain influential even if they don’t endorse the end result.

5. What are China and India doing?

The two economic powerhouses sit in the BASIC negotiating group (representing Brazil, South Africa, India, and China). In May, they committed to work toward a deal and want developed countries to take the lead in emissions. They’re also looking for evidence the richer nations will make good on a 2009 pledge to mobilize at least $100 billion a year in climate-related finance by 2020. India wants additional pre-2020 pledges from wealthy polluting nations.

6. What’s the likely outcome in Bangkok?

Some parts of the Paris rule book are likely to emerge even if the whole package isn’t nailed down. There’s potential that nations will agree on a framework for channeling aid and financing to the poorest nations. Countries including Norway and Switzerland are looking to the carbon market as a possible transfer mechanism that would shift money to developing nations for cutting emissions in exchange for credits that richer nations could use to offset their own pledges.

7. What would failure mean for markets?

No agreement in Bangkok would slow the process of setting up investment channels for greening the world economy. Fund managers and banks are starting to back companies with business plans that match the emission-reduction pace set out in the Paris agreement. Some nations including the U.K. and Norway are already preparing to fund projects to cut greenhouse gases in exchange for credits that can be used to comply with the Paris goals. The Bangkok texts may even imply a higher value for existing UN credits, which have jumped by about a third since April. No progress in setting new market rules risks further increases in planet-warming gases.